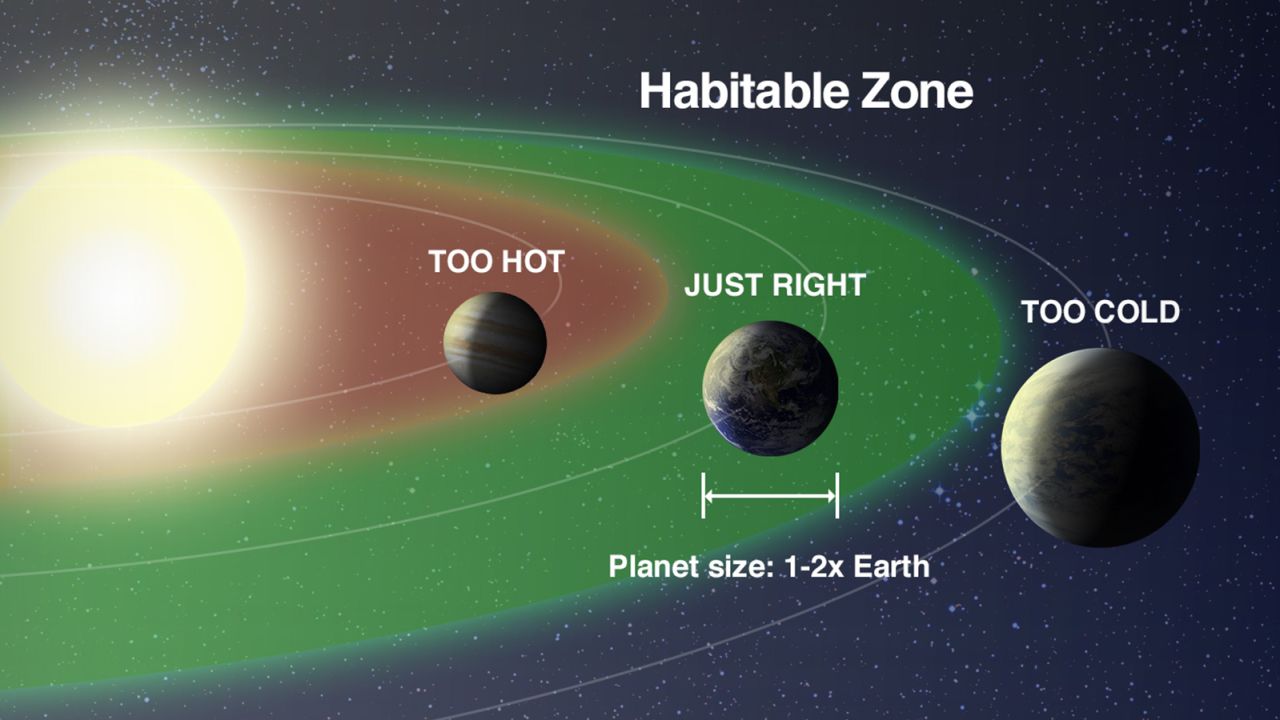

When looking for planets that might support life in our galaxy and beyond, astronomers are looking for conditions that are just right to create the “Goldilocks zone.” This is also called the habitable zone, when a planet is the right distance from its star to have a comfortable temperature and liquid water pooling on its surface.

And as far as we know, life requires water and could exist on planets within the habitable zones of their stars. Now, researchers are proposing that some violent interactions between stars could actually increase the habitable zones for planets orbiting binary, or two-star, systems.

Wonders of the universe

Their study was published Wednesday in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Early in their formation, planetary systems are a harsh, tumultuous place. Stars are born in stellar nurseries, where they are clustered together and often result in violent collisions. Baby planets orbit the stars in disks made of gas and dust. Everything that happens is almost at odds with enabling planetary systems to form.

But this may actually help the habitable zone, according to astronomers at the University of Sheffield. Bethany Wootton, an undergraduate student, and Richard Parker, a Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Fellow, developed a model to look at how the habitable zone changes around binary systems.

Astronomers believe that a third of the star systems in our galaxy, the Milky Way, are made up of two or more stars. The number increases when they consider younger stars.

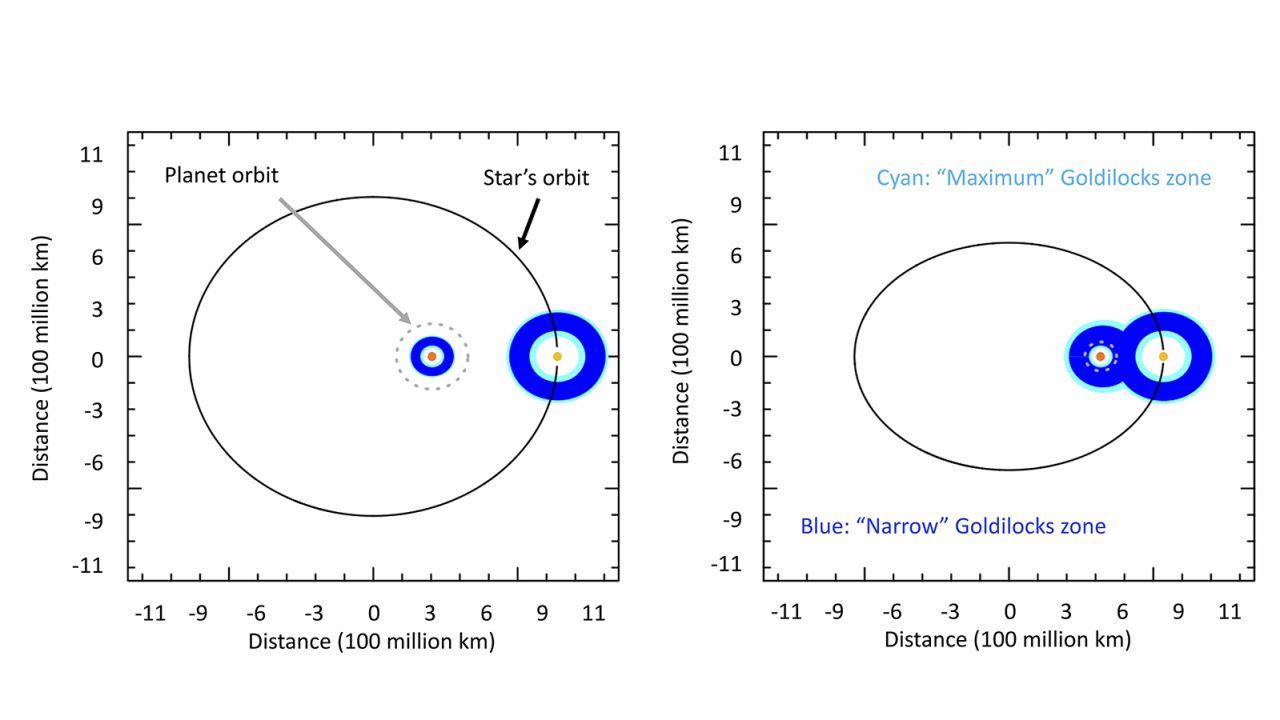

In a system with more than one star, the size of habitable zone for the planet is determined by the stars’ distance from each other. If they are far apart, each has its own habitable zone, based on the radiation from that star. But if the stars are close, their habitable zones are also closer to each other and provide a larger, warmer zone. The larger the zone, the better chance for a planet to find itself in the right spot to support life.

The researchers used simulations to look at clusters of young stars in stellar nurseries, which can contain 350 binaries. Out of those 350, 20 are nudged closer together because of the movements of a third star. And then their habitable zones would expand.

A few of the binary star systems even had overlapping habitable zones, which would increase the chance of a planet orbiting either or both stars to be in the right spot.

“The search for life elsewhere in the universe is one of the most fundamental questions in modern science, and we need every bit of evidence we can find to help answer it,” Wootton said in a statement. “Our model suggests that there are more binary systems where planets sit in Goldilocks zones than we thought, increasing the prospects for life. So those worlds beloved of science fiction writers – where two suns shine in their skies above alien life – look a lot more likely now.”

The quest for the habitable zone also motivated the creation of the Habitable Zone Planet Finder, an astronomical spectrograph that can measure infrared signals from nearby stars and find planets that could support water on their surface. The HPF is at the University of Texas at Austin’s McDonald Observatory and will seek out low-mass planets around cool red dwarf stars, which are known to host rocky planets. The new planet finder began operating in February.