Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Global Economy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

It is just under four years since the world became aware of Covid-19. This triggered a huge decline in economic activity, followed by a swift overall recovery, the Russia-Ukraine and now Gaza wars, soaring prices (especially of food and energy) and rapidly rising interest rates. In the background, climate change is becoming increasingly evident. What does all this mean for the world’s poorest? The answer is that past progress in eliminating extreme poverty has slowed sharply. In the countries that contain most of the world’s poorest people, it has simply stalled. If this is to improve, these countries will need more generous assistance from official donors.

The much-maligned age of globalisation helped bring about huge reductions in the proportion of the world’s population living in extreme destitution. Currently, the World Bank defines that as an income of less than $2.15 a day at 2017 prices. The numbers in extreme poverty, so defined, fell from 1,870mn (31 per cent of the world population) in 1998 to a forecast of 690mn (9 per cent of global population) in 2023. Unfortunately, the rate of decline has slowed sharply: from 2013 to 2023, the global poverty rate will fall by a forecast of a little over 3 percentage points. In contrast, it fell by 14 percentage points in the decade prior to 2013. (See charts.)

Why has this slowdown in the rate of fall in extreme poverty happened? The answer is that it has slowed in the world’s poorest countries — those eligible for lending by the International Development Association, the World Bank’s soft-lending arm. The proportion of the population in extreme poverty in the rest of the world fell from 20 per cent in 1998 to a forecast of just 3 per cent in 2023. It fell by an estimated 4 percentage points just between 2013 and 2023. Meanwhile, in the IDA-eligible countries the proportion in extreme poverty also fell, from 48 per cent in 1998 to a (still high) forecast of 26 per cent in 2023. But the reduction was a mere percentage point between 2013 and 2023, while it had been 14 percentage points in the preceding decade.

It is not that extreme poverty has disappeared altogether in better off countries. There are still forecast to be some 193mn in that condition in countries ineligible for IDA today. But the number in IDA-eligible countries is 497mn, 72 per cent of the global total of 691mn. Moreover, with the proportion of extremely poor in the rest of the world just 3 per cent, it is reasonable to assume that, with modest overall growth, this will be mostly eliminated by 2030. It is clear, then, that the goal of eliminating extreme poverty from our world will only be achieved by focusing attention and resources on the world’s poorest countries, where the bulk of the extreme poverty is concentrated and where it is also most entrenched.

Seventy-five countries are poor enough to be eligible for IDA resources. Of the 75, 39 are in Africa. Some of them are also eligible for borrowing on the more expensive terms of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development as well. These include Bangladesh, Nigeria and Pakistan.

There is little doubt that IDA-eligible countries include many of the worst managed ones in the world. But they are also fragile in multiple ways and so are caught in poverty traps, from which it is desperately hard to escape, especially when buffeted by shocks, as they have been. Moreover, they need not be “bottomless pits”. IDA was created more than half a century ago in large part to help India. Indeed, IDA was sometimes even labelled the “India Development Association”. Yet India has now successfully graduated and is a donor. Indeed, IDA has a long list of graduates, China also among them.

IDA is now using its 20th replenishment, from July 2022 to June 2025. Given the urgency of accelerating growth, reducing extreme poverty and tackling challenges posed by climate change in impoverished countries, the next replenishment will need to be far bigger, as Ajay Banga, World Bank president, argued at its midterm review.

The World Bank’s latest International Debt Report, out last week, reveals another powerful reason why more IDA resources are needed: these countries have become too reliant on more unreliable and expensive sources of funding. Thus, the report states that “For the poorest countries, debt has become a nearly paralysing burden: 28 countries eligible to borrow from [IDA] are now at high risk of debt distress. Eleven are in distress.” The debt problem is more general. But it is particularly significant in countries with such high concentrations of desperately poor people.

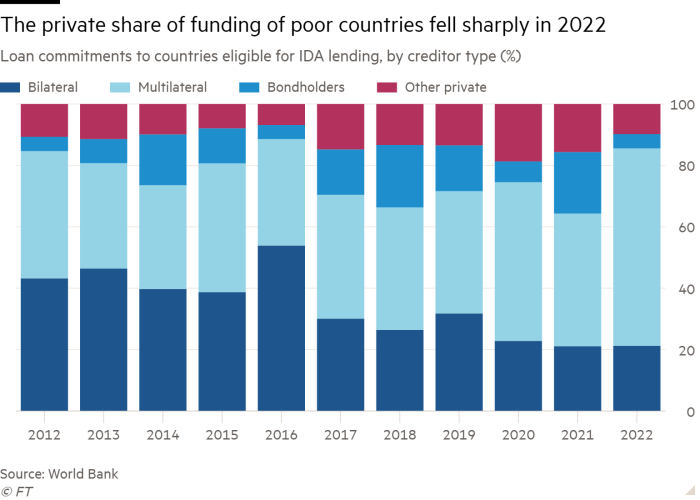

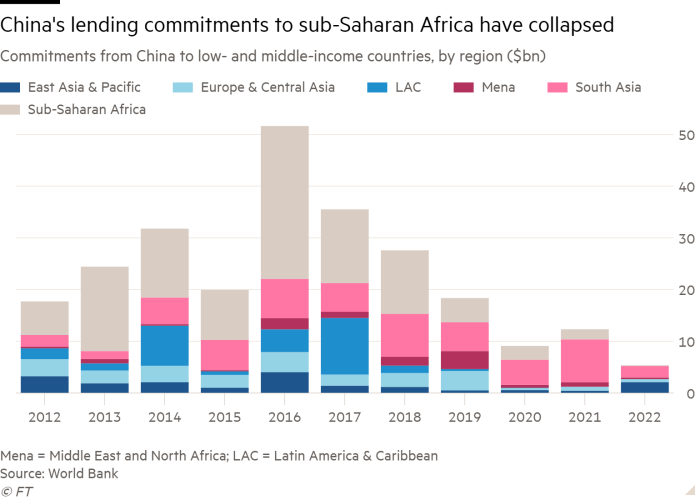

These debt problems are not that surprising. Between 2012 and 2021, the proportion of external debt of IDA-eligible owed to private creditors jumped from 11.2 to 28.0 per cent. Partly as a result, debt service of IDA-eligible countries jumped from $26bn in 2012 to $89bn in 2022, with interest payments alone jumping from $6.4bn in 2012 to $23.6bn in 2022. Above all, the share of bondholders and other private lenders in total commitments collapsed from a high of 37 per cent in 2021 to a mere 14 per cent in 2022. This is classic creditor behaviour in dealing with marginal borrowers: head home when the Federal Reserve tightens monetary policy. In all, the share of IDA-eligible countries at risk of debt distress reached 56 per cent in 2023, says the report.

Commercial borrowing by these countries is simply unsafe. Some of their outstanding debt will need to be written off. More important, they will need far more concessional finance. It is not just the rich countries’ duty, but in their interest to provide the resources they need to escape the poverty trap. Billions of people have done so. Now let us finish the job.

martin.wolf@ft.com

Follow Martin Wolf with myFT and on X